In a perfect world, people with addictions would participate in treatment and never look back. They would begin their recovery initiated during treatment and maintain it after returning home, thus avoiding relapse. But whether we like it or not, relapse is, for many, an integral part of recovery: it is a trial-and-error process.

In this way, recovery is like learning to ride a bicycle: you get on, ride a bit, and fall down. Then you dust yourself off and try again (and again) until you are able to ride without falling. To extend the metaphor further, you can observe others and read manuals about how to ride a bike but until you actually get on a bike you will never learn to ride.

There is, however, a problem with this metaphor. In relative terms, relapsing before the arrival of fentanyl and its analogs was akin to falling off a bicycle and scraping your knee. Now, relapse is more like falling off a bicycle and getting run over by a truck.

We have long recognized that people in recovery are particularly vulnerable to contaminated street drugs (why this is so is explained below). In 2017, we implemented a new policy that required opioid-dependent patients to undergo suboxone treatment. With suboxone, former clients are making it through the ups and downs of post-treatment life and avoiding overdose death.

Compared to methadone, suboxone remains a relatively unknown medication-assisted treatment for addictions. But now, more than ever, Canadians struggling with drug addiction need greater access to suboxone treatment.

Our Contaminated Street Drug Supply

The contamination of the illicit drug supply in Canada has left little room for error when it comes to ingesting street drugs. According to BC’s provincial health officer Bonnie Henry, street drug toxicity is “through the roof … We are seeing very high levels of fentanyl and carfentanil and other contaminants, not only in the opioids on our streets but also in stimulants, and methamphetamines and other drugs.”

Since the BC government declared the opioid overdose crisis a public health emergency in April 2016, over 5,000 British Columbians have lost their lives to overdoses. The crisis shows no signs of ending soon: this past May and June both set records for overdose deaths. In an earlier blog, I wrote about how BC’s other public health emergency (the COVID-19 pandemic) is contributing to the recent spike in opioid overdose deaths. Individuals in recovery are struggling with social isolation and reduced access to addiction treatment and harm reduction services.

North America’s Contaminated Illicit Drug Supply Is Likely Here to Stay

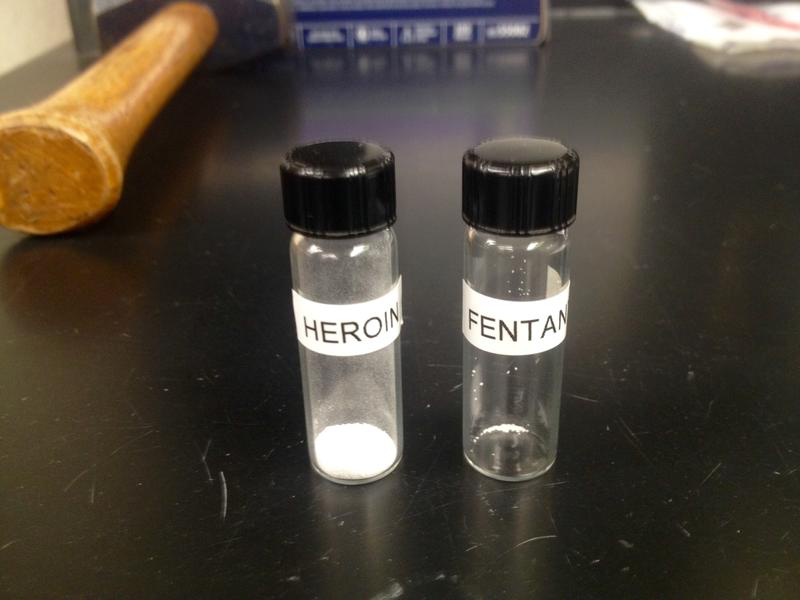

According to the US-based Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin. As little as 3 milligrams (see photo below) can be a fatal dose for an average-sized adult. An analogue of fentanyl known as carfentanil is 100 times more potent than fentanyl, according to the US-based Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). The potency of fentanyl and its analogues means that hundreds of doses can be stashed in a single envelope, making it difficult for law enforcement to detect it in shipments.

Its low manufacturing cost, portability, and high potency also help explain why these drugs are still popular in spite of their overdose risk and why they will likely be available on our streets for the foreseeable future.

Governments are Responding to the Contaminated Drug Supply and Overdose Crisis

Governments across North America have made overdose reversal kits containing naloxone (or Narcan®) available to the public at walk-in clinics, pharmacies, and emergency services (see the Site Finder website for a listing of BC locations where naloxone is available). Recognizing that more needs to be done in light of the recent rise in overdose deaths, the provincial government in BC has also suggested changes to the Mental Health Act to allow youth who overdose to stay in a hospital up to 10 days, as well as create more treatment and recovery beds. Provincial and state governments are also advocating for the decriminalization of personal amounts of opioids and a safer drug supply.

Suboxone – An Important (but Underutilized) Harm Reduction Tool

Another important (but underutilized) harm reduction tool is suboxone. Starting in 2017, we began requiring all clients admitted for opioid addiction to agree to suboxone treatment. Suboxone contains buprenorphine, which prevents withdrawal and craving and blocks other opioids from binding with opioid receptors in the brain. Suboxone also has a low overdose risk and lacks an intoxicating effect (Velander, 2018).

The period after completing treatment is particularly dangerous for former opioid users: “renewed use after abstinence is associated with a high overdose risk, likely the result of the loss of previous tolerance and misjudgment of safe amounts” (p. 23). Research by Nielsen et al. (2016) has concluded that buprenorphine maintenance is “superior to detoxification alone in terms of treatment retention, adverse outcomes, and relapse rates” (cited in Velander, 2018, p. 24).

Unfortunately, suboxone treatment is hard to come by in Canada, even though other countries approved it for addiction treatment dating back to the 1990s. A 2017 CBC story reported that only 3% of physicians in BC prescribed suboxone. Approved in early 2019, Sublocade, an injectable version of suboxone, made it possible for patients to switch from daily to monthly treatments. In July 2019 the government of Alberta reclassified suboxone to make it easier for physicians to prescribe it. However, based on our own challenges locating doctors willing to continue prescribing suboxone to our clients returning home, it appears that more needs to be done to promote its use in Canada.

How the Shame of Relapse is Contributing to the Opioid Overdose Crisis

We are also aware of how former clients struggle with shame when they relapse after treatment. Shame is a powerful, negative emotion that can compel former clients to use alone rather than reveal to friends and family that they have relapsed. According to the Harm Reduction Coalition, using alone greatly increases the chance of fatal overdose since no one is there to resuscitate its victims with Narcan or call 911 if they pass out.

The shame of relapse also makes it less likely that a person in recovery will reach out for help, which means that they will continue to engage in using dangerous street drugs in the future. Doing so is akin to playing Russian roulette with a loaded pistol. So the shame of relapse is another reason why suboxone treatment is mandatory for opioid-dependent clients who attend Sunshine Coast.

Pass Legislation to Make Suboxone More Accessible to Canadians Struggling with Opioid Addiction

Ultimately, our suboxone policy is there because we recognize that it can prevent needless, preventable deaths due to opioid overdose. As a treatment, however, suboxone remains difficult to access for most Canadians. Most of the legislative changes to provide greater access to opioid replacement therapies have focused on methadone and pharmaceutical-grade hydromorphone. For example, the provincial government in BC has taken measures to allow take-home, safe supplies (“carries”) of both of these drugs. Previously, drug users had to line up at pharmacies on a daily basis for these treatments.

BC Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Judy Darcy indicated that plans were afoot to support physicians and nurse practitioners across the province to adopt the new carry guidelines. In July, the federal and provincial governments initiated a $2-million pilot project to issue free pharmaceutical-grade hydromorphone to people at risk of overdose in the Cowichan Valley on Vancouver Island. Based on our positive experience with suboxone, we hope that the government will do more to establish it as a medical treatment for addiction.

References

Velander J. R. (2018). Suboxone: Rationale, Science, Misconceptions. The Ochsner Journal, 18(1), 23–29.